Interview with Dr. Salah Eddin Al Djazairi

Dr. Salah Eddin Al Djazairi has lectured and researched at the University of Constantine (Algeria) for more than ten years. He also tutored at the Department of Geography of the University of Manchester. More recently, he has worked as a research assistant at UMIST (Manchester) in the field of history of science. Dr Salah has published many academic works.

Publications in scientific journals include papers on environmental degradation, and desertification, as well as papers on politics and change in North Africa, and problems of economic and social development.He has also contributed historical entries to various encyclopaedias such as the Columbia Gazetteer, Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Francophone Studies.

S.O.: What were the social, political, religious dynamics of rise of Muslim Andalusian civilization in the medieval age?

S. E. Al Djazairi: The scientific upsurge in Al Andalus was generated by a number of factors. During the golden age of Islamic civilisation, beginning in the case of Al Andalus in the 8th century, and ending (with the exception of Grenada) in the 13th century, the scientific and cultural upsurge was generalised to the whole Muslim world. Other than Al Andalus, Baghdad, of course, but also other centres such as al Qayrawan in Tunisia, Ghazna (under the rule of Mahmud), Sicily (during Muslim rule), Cairo, Damascus, Khwarizmi, Persia (under Seljuk rule), etc… all were great centres of civilisation.

The reason was that the impetus provided by Islam for science, culture, universal learning, trade, arts, etc, transformed each part it reached. Local cultures were also enriched by the constant arrival of new ideas. Muslim scholars travelled from the far corners of Al Andalus to China, and on the way, or during the Hajj pilgrimage, they exchanged ideas and information about the latest works, scientific theories, and also carried architectural ideas, new plants, farming techniques, etc. In this regard the latest works or techniques found in the East could soon be found in Al- Andalus, and vice versa.

Many local rulers and enlightened elites also promoted scholarship and scholars. Al-Hakam’s library is said to have counted nearly a million books at a time when the largest library in the Christian West had no more than 400 works. The Almohad ruler, Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Mansur (r.1184-1199) built in Seville the Giralda which became used as an observatory.

He also greatly sponsored scholars at his court. Other Spanish rulers, including Abd Er Rahman I (731-786), were great garden lovers, collected plants, and were behind the creation of botanical gardens, which were later imitated in Europe.

In those days, scholars were the favourites in palaces and in the houses of the rich. The stories that reach us about the welcome offered to scholars in some places are quite remarkable. In Al Andalus, rulers such as Abd Er Rahman III (caliph 912-961), his son Al-Hakam II (ruled 961-976), Ibn Abi Amir (938-1002), the Banu Di Nhun of Toledo especially al-Mamun (ruled 1043-1075), were great lovers of learning, and they greatly sponsored scholars.

A final element that helped science and culture flourish in Al Andalus was that there, as in the rest of Muslim world, excellence and creativity of the mind were highly appreciated, books and reading were much loved by society as a whole, and the scholar, before the rich and before the sportsman and the pop-star of our day, truly occupied the highest rank in society.

S. O.: What kind of scientific researches and development have been made in Andalusian civilization?

S. E. Al Djazairi: Al Andalus contribution to the upsurge of modern sciences and civilisation constitutes one of the major landmarks of human civilisation. To even seek to outline this contribution is impossible in such a short space. Suffice it to say that at its peak, around the rule of Abd Er Rahman III, Al Andalus was the place of rendez vous for all Europeans who sought learning and to have a glimpse at the civilised and the advanced. Envoys came to

Muslim Spain to take books on astronomy and mathematics back to Christian Europe. Spanish Christian rulers and princes such as Sancho the Fat came to Cordoba to seek medical help. It was in Muslim Spain where the best engineers, irrigation specialists, tool makers, glass and ceramic makers, builders, etc were to be found.

In terms of particular sciences, in astronomy, for instance, the works by Al-Zarqali, Al-Bitruji, and Jabir ibn Aflah, in particular, were at the centre of the astronomical breakthroughs in Europe.

In medicine, the pioneering works of the Ibn Zuhr family, a whole generation of doctors, and the surgical instruments devised by Al-Zahrawi, were for centuries ahead of anything of the kind in Europe, and they revolutionised modern science. Spain produced by far the largest number of pharmacists and herbalists in the world for centuries. The names of Ibn al-Baytar, al-Ghafiqi, Ibn Juljul, etc have remained with us to this day, and their works still offer a lot to modern science.

Spanish men of literature such as Ibn Hazm, and historians such as Ibn Hayyan and Ibn al-Qutiya, and the countless other men and women who have graced the field of Spanish

Muslim literatures are the source of much of what we know about modern thought and literature.

Farming manuals by Ibn al-Awwam, Ibn Bassal, etc. were centuries ahead of any books on similar subjects. These authors studied farming in all its intricacies, and offered knowledge of, and solutions to, problems which are still with us. They also explained the planting, harvesting and storage of various crops such as wheat, rice, and cotton.

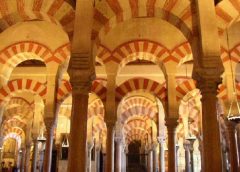

Spanish industries such as paper making, ceramics, tools, shipbuilding were the most advanced of the age, too. Muslim Spain has left us an architectural legacy which is still the wonder of millions of tourists, from the Alhambra in Grenada to the Giralda in Seville, to the Cordoba Mosque, everywhere; tourists today are dazzled by the creative genius of Spanish Muslims.

Spanish Muslim engineers, likewise, have built structures, such as bridges, fortresses and dams, which survive till our day, and which were feats of engineering unequalled for centuries, except by the Ottoman Turks.

Muslim Spain also offered a great model of toleration where people of various faiths such as the Christians and Jews not only lived peacefully alongside Muslims but also achieved very high status; this level of tolerance was only matched later in Ottoman Turkey, and only now in the modern Western world.

S. O.: How did the Andalusian civilization influence the continental Europe in terms of science, culture and education?

S. E. Al Djazairi: The impact of Muslim Spain on modern Western culture is also a vast subject which can only be given justice in a very large work. Here, it is worth noting that, when the first men of learning in the West such as John of Gorze (900-974), the ambassador of the German Emperor sought modern science, they travelled to Spain.

John spent three years in Cordoba, there acquiring Muslim knowledge of astronomy, in particular, before taking some manuscripts back with him to Gorze in Lorraine (modern

France). Soon Lorraine became the precursor and leading region in astronomical knowledge in the whole of Christendom, and from there this knowledge spread to France, Switzerland, and above all England.

A few decades after John of Gorze, the next great scholar to travel to Spain was Gerbert, the future Pope Silvester (d.1003). Gerbert was more interested in mathematics, and spent a long time in Catalonia, at the Monastery of Ripoll, collecting mathematical knowledge derived from Muslim works, more especially the knowledge of the numeral system. On his return to France, Gerbert caused a great stir by the introduction of this new learning which dumbfounded the minds. He was accused of being a sorcerer, and his mathematical knowledge was so advanced it was equated with ‘Saracen Magic.’ In 1064 crusading forces made of Spaniards and Frenchmen captured the town of Barbastro. Following this capture they took with them north thousands of Muslim craftsmen who were divided between European countries, including Byzantium.

These craftsmen became some of the great artisan builders transferring Muslim know-how to

Christian powers. Christians who lived under Muslim rule also transferred many techniques and trades in the Christian world. Many buildings in south Western France, for instance, owe to these Christians who carried the skills from Muslim Spain to Christian Europe.

The greatest impact of Muslim learning on the rest of Europe took place following the capture Toledo in 1085 by the Christians.

In Toledo the Christians came across the large libraries of the Muslims filled with scientific works. Soon a great translation effort of Muslim scientific books took place from Arabic into Latin. The great works of Ibn Sina, Al-Farabi, Al-Zahrawi, Al-Razi, etc. were there translated, and they soon gave the foundations to modern learning and science.

The Jews played a large part in this translation effort because they mastered both Arabic and Latin, and so assisted the many Western scholars who came to Toledo in order to translate these works. Subsequently, victorious Christian rulers, such as Alfonso X of Castile (1221-1284), once he retook Seville from the Muslims, in 1248, constituted schools of learning, where Muslim science played a central role. His Libro del saber, for instance, is a large treatise of astronomical and mechanical knowledge primarily derived from Muslim science.

Following the capture of most of all Al Andalus from the Muslims by the middle of the 13th century, Muslim craftsmen were retained to run many industries, most particularly the paper and sugar industries. Muslim skills were also retained in farming. Muslims and their knowledge of seafaring were also used in the Spanish and Portuguese navies, and their knowledge was crucial to the great discoveries of the late 15th and 16th centuries.

S. O.: What are the causes ofdecline of Muslim Spain?

S. E. Al Djazairi: In Muslim Spain, the causes of decline go back to the early 11th century. In 1003, Ibn Abi Amir, named al-Mansur died. Al-Mansur was a great ruler and military leader. His son, however, was very weak, and soon after he assumed his rule, Muslim Spain disintegrated into anarchy and chaos. Soon it broke into thirty or so independent states, the Reyes de Taifas as they are known. These states soon began to fight each other. Profiting from their wars, the Christians began the so-called Reconquest. When Barbastro fell, soon followed by Toledo, the Reyes, or Muslim petty rulers began to feel threatened. They called the Almoravid ruler, Ibn Tashfin, to their defence. Ibn Tashfin crushed the Christian armies in 1086 at Zallaqah, and managed to keep Spain and Portugal in Muslim hands for more decades. Soon his successors fell in the same condition of divisions and started fighting each other, which encouraged a new wave of Christian conquest. This time the Almohads intervened and again saved Spain and Portugal for the Muslims, especially after the victory by Abu Yusuf Ya’qub Al-Mansur at Alarcos in July 1195.

Al-Mansur was succeeded by weak rulers, and again Muslims fought each other, and again the Christians advanced on Muslim territory. When the Christians won the victory of Navas de la Tolosa in 1212, this meant the end of Muslim power in Spain. Soon after Muslim territory was captured, the Muslims losing their strongholds of Valencia, Cordoba, etc, and finally Seville, their capital falling in 1248. Only Grenada remained in Muslim hands until 1492 when it, too, fell in Spanish Christian hands. When the Muslims lost their political and military power, their culture, faith, and their scientific power retreated, or were suppressed, until the Muslims, and their subsequent descendants, the so-called Moors, were removed from Spain in the years 1609-1610.

S. O.: Considering the dire situation of Muslims of today, how can we model Andalusian Muslims? What do we need to do?

S. E. Al Djazairi: The solution is very complicated and simple at once: we simply need to believe in ourselves, that what we could achieve in the past we can achieve again, and we should not be afraid of the challenges and the big ideas. Fear, hesitation, accepting the mediocre, lack of scientific research, feeling inferior to others, dependency on the state for everything, lack of self-reliance, these are the enemies of progress, and our enemies. The day when those with big ideas take the forefront again in the Muslim world, then we would have made a great step to greatness again. We need also a great scientific upsurge reinforced and safeguarded by the ethics of our faith, for power without moral ethics also leads to collapse.

Given the reference made to Ibn Hazm in the aforementioned article, please note that some of his title are now available in English for the first time:

a. A Ruling on Music & Chess (expanded second edition)

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Ruling-Music-Chess-Ibn-Hazm/dp/1975749235/ref=sr_1_3

b. Foundational Islamic Principles

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Foundational-Islamic-Principles-Ibn-Hazm-ebook/dp/B0753Z7RBB/ref=sr_1_2