The word “namazgâh” – which means ‘place of prayer’ – is a compound of Persian word ‘namaz’ and preposition ‘gâh’ – which mean prayer and place respectively. Muslims have esteemed the prayer (i.e. salah) very much for centuries. And they have not neglected this worship even in the most difficult conditions including travelling.

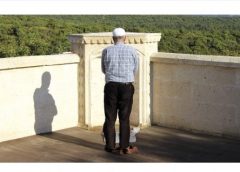

In Ottoman times, the places that were built in the countryside where there was no nearby mosque or masjid were called ‘namazgah.’ They are outdoor places of worship that are mostly used in summers and allocated for the well-attended prayers like Friday, Tarawih, Eid al Fitr and Adha. They are graded as a smooth surface that is a bit higher than the ground level. Their floor can be grass or soil; stones are also used.

As an old tradition of Islam, ‘namazgahs’ are places of worship for Friday, Eids and Tarawihs, places where people socialize, and places for festivals. They make it easy for Muslims to perform their worship.

Some namazgâhs have minbar (pulpit). Because of the need for wudu (ablution), namazgâhs are either built with a fountain or well, or they are built at a place where there is a fountain already. They also have served the travellers; there used to be plane trees or hackberries for resting and comfort.

Other side of the stone of mihrab (niche) of some namazgâhs are like fountains. The stone of mihrab, which indicates the qibla (i.e. the direction of Kaba), and is a cover between the worshipper and the passer by, looks like a tombstone. Usually, it is written on them a part from the verse 3:37 “كلما دخل علیها زكریا المحراب” and sometimes only the word “المحراب” and sometimes “Fatihah for the soul of the owner of the charity.”

The first special, and nice, reason for the abundance of namazgâhs is to remember and keep alive the fond memories of “the prayers performed all together in open field” at the first years of Islam when the foundation of the State of Madina was laid, and to continue this Sunnah. The second reason is to show the strangers the qibla, who are travelling or having a picnic and have difficulty in deciding the direction of the qibla.

As a matter of fact, namazgâh is not a tradition peculiar to the Ottoman. Muslims have used every place for worship as long as the place is clean. Our Prophet (asw) also prayed in open fields. These places later have been transformed into namazgâhs.

Our Master Muhammad (asw) sometimes performed Friday and Eid prayers in the open field near the Masjid an-Nabi. It is narrated that when he prayed in that field, a cloud used to shadow him. For this reason, when Omar b. Abdulaziz built a masjid in this field as Madina Governor, it was named Masjid al Ghamama (Masjid of the Clouds). Moreover, a namazgâh was built on the hill of Abu Qubays where the miracle of the splitting of the moon occurred.

The first four caliphs (ra) also performed prayers in the open field of the same neighbourhood like our Prophet (asw). Today, there are mosques named after the first four caliphs in those fields.

Having taken our Prophet (asw) and the first four caliphs as examples in many cases, the Ottoman followed the tradition of namazgâh and built many of them.

City namazgâhs used to be built on the places of destinations in order to meet the need for worship and resting while travelling. The ones in the city centres were built with a few trees with the aim of making the worship easier in summers.

The ones on the roadsides used to be built as the places to meet the need for worship and resting and where people gather to make rain prayer. Those going to Hajj or military service used to be sent off from those namazgâhs. The Evening (‘isha’) and Tarawih prayers used to become unforgettable with unique pleasure of spirituality under the moon and stars.

The function of the namazgâhs was not just providing a place of worship. It is known that they were on the way of caravans and recruitment before military expeditions. There were one hundred and fifty three namazgâhs in the records in Istanbul; but none of them reached today. Fifty namazgâs are mentioned just in Üsküdar district.

Namazgâhs continue to serve as examples of a great civilization that has come from the past.